Implications of the FCA’s ‘polluter pays’ proposals for firms that have advised on pension transfer

28 February 2024

Sarah Abraham, who leads First Actuarial’s pensions redress team, discusses the FCA’s consultation paper on redress and what it might mean for personal investment firms. This article was originally published in FT Adviser.

The FCA’s consultation paper CP 23/24: Capital deduction for redress: personal investment firms, issued in November 2023, could have significant implications for personal investment firms.

What is the FCA proposing?

£760m in redress was paid by the Financial Services Compensation Scheme (FSCS) due to unsuitable advice given by personal investment firms (PIF) between 2016 and 2022, the FCA has found. An astonishing 95% of this redress involved only 75 firms.

In light of this finding, the FCA wants polluter firms who have “got things wrong” to hold sufficient funds to meet their own redress obligations, rather than effectively passing the cost to other firms through the FSCS levy.

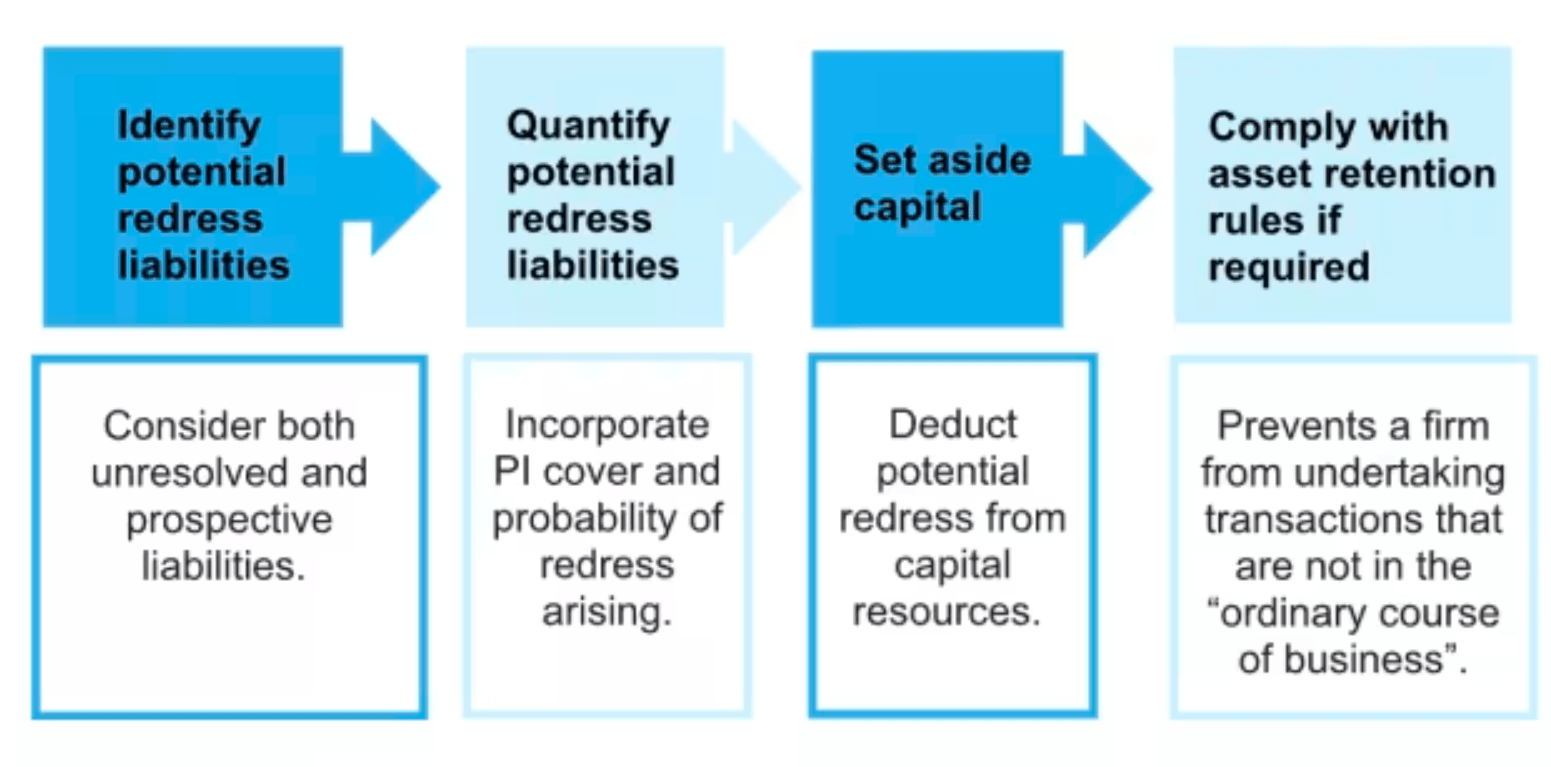

The FCA is proposing to require PIFs to set aside capital for potential redress liabilities arising from designated investment activities. The calculations would allow for a probability factor, reflecting that not all potential redress liabilities will result in a redress outcome.

The capital to cover potential redress liabilities would be deducted from the firm’s capital resources. If the firm is undercapitalised after this deduction has been made, it will have to comply with asset restriction rules. These rules would prevent the firm from carrying out transactions not deemed by the FCA to be “in the ordinary course of business”.

The FCA will also use new reporting requirements to direct their supervisory process. Firms will need to provide the aggregate value of redress liabilities and the number of consumers affected. They will also be expected to keep records of how they have arrived at their stated redress liabilities.

Alongside the “polluter pays” proposals, the FCA is consulting on a wider review of the regulatory regime for PIFs. The aim is to move towards a more comprehensive regime that would incorporate:

- New regulatory rules around capital and liquidity adequacy

- Improved risk management requirements

- More extensive reporting and disclosure requirements

- Wind down planning requirements.

The consultation was accompanied by a ‘Dear CEO’ letter, reminding firms not to avoid their redress commitments.

When will the changes take effect?

The changes are expected to come into effect in the first half of 2025.

The consultation closes on 20 March 2024, and the FCA plans to issue a Policy Statement in the second half of this year. There will then be a period of at least six months for firms to prepare for the changes.

Which firms are affected?

The FCA expects around 4,900 firms to fall within the scope of the proposals.

Exemptions will apply for some PIFs – most notably sole traders and unlimited partnerships. However, exemptions for these firms will only apply to the asset retention requirements. This means that they will still be expected to identify and quantify their redress liabilities, and to report to the FCA on their findings. They will then decide on the need for any action, such as imposing bespoke asset retention requirements on firms that are assessed to be undercapitalised.

A broader exemption will apply to PIFs that are part of a group and are subject to group supervision by either the FCA or the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA). Such firms would need to notify the FCA that they will be making use of the exemption, and outline how the group assesses and holds capital for the risks posed.

How will firms be expected to identify cases that may give rise to redress?

Potential redress liabilities will fall into two categories:

- Unresolved redress liabilities: Where the firm has received, but not resolved a complaint. This includes complaints under review by the Financial Ombudsman Service (FOS).

- Prospective redress liabilities: Where the firm has identified recurring or systemic problems, or foreseeable harm that could give rise to an obligation to provide redress.

In practice, identifying unresolved redress liabilities should be relatively straightforward as firms will have records about any complaints already received.

Identifying situations that may result in prospective redress liabilities may be more challenging. The FCA considers that firms should already be aware of cases of potential harm as part of their compliance with Consumer Duty. However, given that this process will be largely self-regulated, there may be inconsistencies in the way that firms identify and quantify their exposure to risk.

Why are the FCA’s proposals a particular concern for firms that have advised on pension transfer?

There are several aspects of the proposals that will be particularly onerous for firms that have given pension transfer advice:

1. Redress arising from pension transfer advice can be significant. Indeed, the FCA notes in its consultation document that between 2012 and 2022, 83% of PIF FSCS costs arose from advice on self-invested personal pensions (SIPPs) or pension transfers. This means that firms that have provided this sort of advice are likely to identify higher levels of potential redress liabilities and are thus more likely to be impacted by asset retention rules.

2. Establishing a suitable estimate for potential redress associated with pension transfer is difficult. This is particularly true of redress relating to defined benefit transfer, which is highly sensitive to the circumstances of the case and depends on multiple factors – such as the date the transfer was effected, the occupational scheme that the consumer transferred out of, and the investment strategy adopted for the transfer proceeds. Firms may find they need specialist actuarial support to assess their exposure to potential future redress payments, and this could be costly.

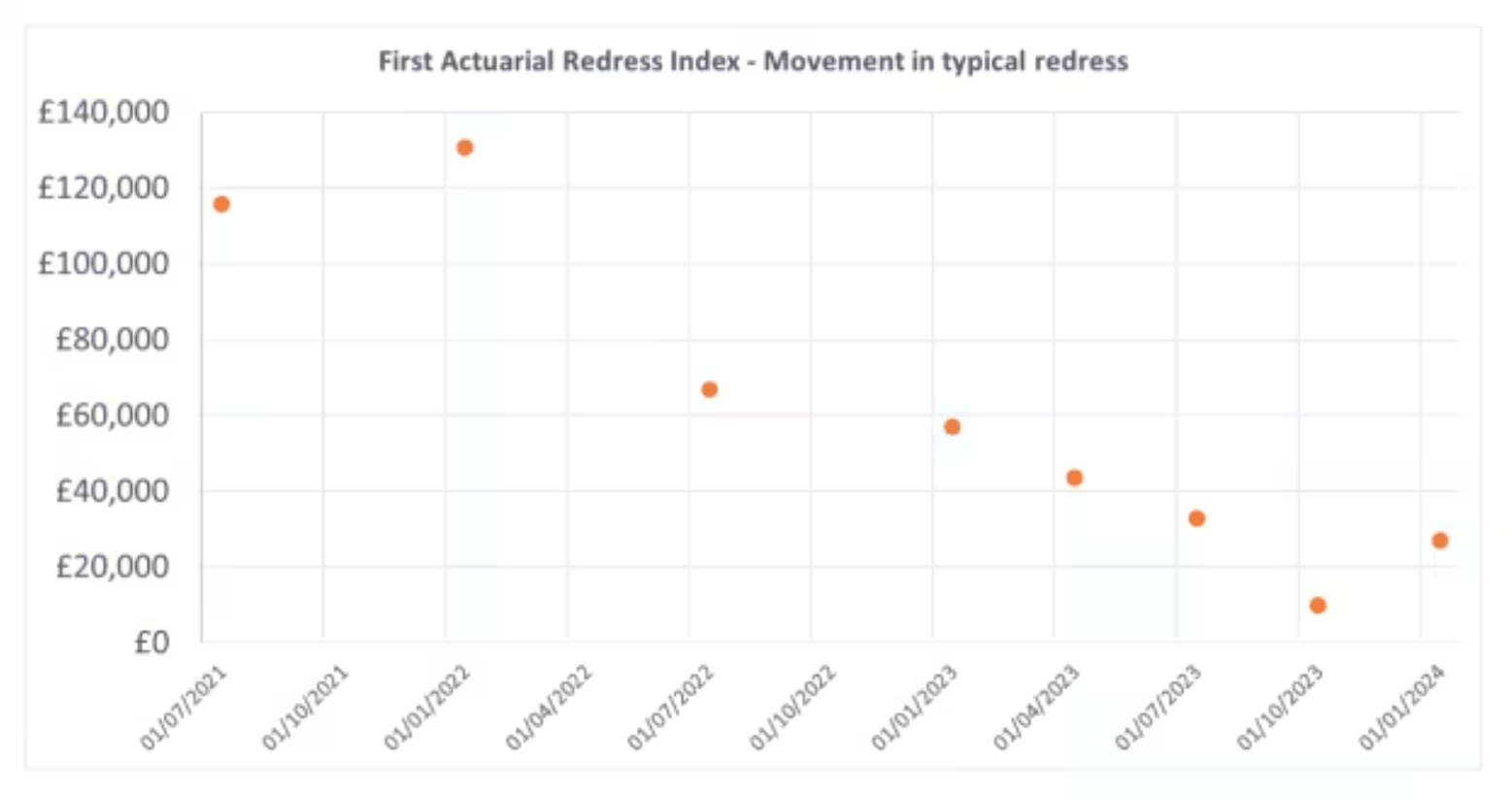

3. A particular challenge of defined benefit transfer redress is that it depends on market conditions as at the first day of the quarter, and can vary materially from one quarter to the next. The First Actuarial Redress Index, shown below, tracks movements in average redress on pension transfers that took place after 2015 – and clearly shows how variable redress can be. It’s worth noting that redress for earlier transfers, such as those paid in the 1990s and 2000s, tends to be much higher, although the broad pattern of falling redress over the past few years will also be mirrored in those cases.

Modelling shows typical redress for a 50 year old who had a pension of £10,000 pa in 2015, transferred out in 2017 and invested the transfer proceeds in a mixed portfolio of assets

Because redress has to be recalculated before a final settlement is made, even if it is estimated “accurately” as at a given date, it won’t necessarily reflect the amount that a firm ultimately has to pay out. It’s worth bearing in mind that complaint resolution can be a lengthy process – it can take a year for cases referred to the FOS to reach an initial decision and, if the case is then referred to an ombudsman, a final decision may take a further 12–18 months.

Firms are required to have adequate financial resources at all times. This may mean that they need to incorporate margins for prudence into their estimated redress figures or revisit their redress calculations regularly. Firms that choose the latter will need to be able to identify every scenario in which redress could increase, or seek actuarial support to help them.

4. It will be permissible to allow for professional indemnity insurance (PII) cover in the calculations. This may prove a pragmatic solution for some firms – for example, they may be able to set aside sufficient capital to cover their policy excess on each unresolved or prospective redress case. However, it will be important to be mindful of exemptions – for example, some policies exclude defined benefit transfer advice written to younger individuals – and limits of cover. As noted, redress on pensions transfer can be significant, so there may well be instances where the PII cover is not sufficient to meet all potential redress liabilities.

5. The probability factor built into the calculations will (in the absence of specific agreement from the FCA) need to be at least 28%. However, a higher percentage (leading to higher capital) will be required if a firm has reason to believe that applying the 28% figure would understate its exposure to future redress. This could be the case if the firm knows that a higher proportion of past complaints against it have been upheld. It can be difficult to defend against complaints about defined benefit pension transfer, particularly where the advice was given some time ago – gaps in data often mean that the adviser is unable to demonstrate suitability of advice. There is scope therefore for the probability factor to be significantly higher than 28%, particularly for firms that advised on defined benefit transfer. There is also scope for the probability factor to change over time (as complaints are received and resolved), resulting in unexpected swings in capital requirements.

6. As part of its narrative about potential future regulatory regimes for PIFs, the FCA moots the need for higher capital requirements based on the activities conducted by a given firm. This would mean that firms that have given “high-risk” pensions transfer advice would see increased capital requirements as well as potentially higher liquidity requirements.

Given the above, firms may revisit their offering and decide to cease providing pensions transfer advice. This would have implications right across the financial advice and pensions industries.

The legal requirement for specific financial advice before a defined benefit transfer can be implemented is particularly relevant here. If fewer advisers are available to provide this advice, people may either be unable to transfer out of their defined benefit pension or will only be able to do so at considerable cost.

The FCA references its Advice Guidance Boundary review (AGBR) at various points in the consultation paper. However, it is difficult to see how the AGBR can address this issue unless legislation is amended to remove the requirement for financial advice before defined benefit transfer. This seems improbable given:

- The high risks associated with such activity

- The FCA’s broad stance that transferring a defined benefit pension is unlikely to be in the consumer’s best interest.

What can firms do now?

Ahead of any regulatory change, firms can prepare in a number of ways:

1. Understand how redress works

The FCA is clear that in order to comply with Consumer Duty, firms must monitor consumer outcomes, handle complaints fairly and identify systemic issues in advice. Firms are also expected to understand the risks they are exposed to and to hold appropriate financial resources to meet those risks.

Therefore, a key step that firms can take now – which would be advisable irrespective of whether the proposals set out in CP23/24 are ultimately implemented – is to gain a robust understanding of redress. For firms that have written defined benefit pension transfer advice this might mean training relevant individuals on the factors that influence redress.

2. Gather data about legacy pensions transfer advice

It is good practice for firms to keep records of the pensions transfers they have advised on as they build a picture of their redress risk. Pulling together summary data about each case (such as the transfer value paid, date of transfer and client’s age) is a good starting point. For firms that have written defined benefit transfer advice, it may be a good idea to start gathering more detailed data, such as information about the ceded pension, so that any holes in the data can be identified and steps taken to fill them.

3. Understand the magnitude of redress risk to which they are exposed

It may be helpful, and a matter of good governance, to get a rough estimate of the redress risk the firm is running. In the case of defined benefit transfer advice, firms may want to speak to their actuarial advisers about how best to assess their exposure to redress. There are cost-effective ways of doing this that do not involve a full redress calculation for each “at risk” case.

4. Speak to the PII insurer

Firms will need to understand their PII cover in order to integrate this into their calculations. It is also crucial that firms make their PII insurer aware of any planned suitability reviews so they do not inadvertently trigger the exclusion of cases from PII cover.

Sarah Abraham leads the pension redress team at First Actuarial and has extensive experience in calculating redress in relation to non-compliant pension transfer advice.

This article was originally published in FT Adviser. Reproduced with permission.

Read First Actuarial’s response to the FCA consultation.